Nature in the Political Landscape: The Nature Agenda in the upcoming UK elections, with a brief reference to India

Change your leaders, not your light bulbs.

Thomas L. Friedman, October 21, 2007 New York Times

The rise, and rise, of the Green Party in the run up to United Kingdom’s May 2015 general elections invites the thought whether this is indicative of nature and environment issues being mainstreamed in the political landscape. This paper is an attempt to understand this, by analysing how much nature and environment issues feature in electoral debate, particularly in UK.

UK’s forthcoming election promise to be different, exciting with new, smaller players in the fray along with the traditional parties, Labour and the Conservative (Tories), who currently run a coalition government—the first since 1945—with the Liberal Democrats (Lib Dems) as a minority partner. These parties include the Scottish National Party, Plaid Cymru (Wales) and of course, the Greens.

Of all the above, the rise of the Green Party has been the most dramatic, its membership has crossed the 50,000 mark — swelling by 28 per cent in 2014 , and has overtaken both the Lib Dems; and the UK Independence Party (UKIP). During the same period, the party’s youth wing, ‘Young Greens’ has seen a 100 per cent jump in membership. From a marginal player, which polled barely one per cent in the 2010 election, it is predicted that the Greens may win 11 per cent in the polls next May .

But does the rise of the Greens imply that environment has finally entered mainstream politics in the UK, or is it spurred largely by “an enormous, and almost universal sense of dissatisfaction with major political parties” —or more likely a combination of both factors?

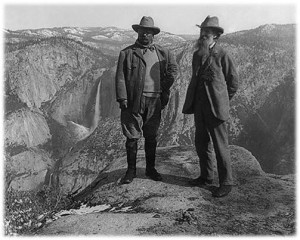

Let’s first try and understand where UK’s political parties stand on issues concerning ‘nature’ conservation. As an aside, it’s interesting to note that the UK has historically not seen any towering leadership in environment, a fact commented upon in the foreword of Against Extinction by the Earl of Cranbook, “The UK, to its detriment has lacked a Teddy Roosevelt.” The 26th President of the United States was only as a powerful statesman, but a pioneering leader in conservation.

Obviously, the Greens have environment issues-ranging from Climate Change, protecting natural resources from short term corporate interests to strict animal protection laws as a core agenda . Their base is increasingly broader, with the party focusing on issues of social justice, welfare, free health and education, a stable economy, equitable society, opposing privatisation of public services, though some of these, including their economic policy has come under severe criticism . At the other end of the spectrum is the UKIP, which is to the UK, what the Republican is—currently—in the USA. To illustrate, a poll showed over 58 per cent of congressional Republicans in the US refuse to accept the science of climate change . The UKIP appears to have adapted this as a party principle, and have pledged, among other things, to repeal the Climate Change Act, and also hint at rolling back clean technologies and green policies. The Lib Dems, on the other hand, are likely to push for green issues, and their pre-manifesto includes introducing new laws to protect the environment, including a ‘Nature Bill’, which will set legal targets for clean air, water, biodiversity, establishing new marine and coastal reserves.

The Labour Party is largely viewed to be lukewarm on green issues. While they enacted the landmark Climate Change Act, 2008 in their last term, a major share of the credit is grabbed by the Tories, who as opposition, played a pivotal role in pushing the Act through. Labour, it is felt, has failed to take a leadership role on the environment, “if Labour put the issue high on the political agenda, the coalition would find it harder to disregard the environment and the need to build a strong low-carbon economy.”

Which brings us to the Tories, the current government in power, and the Prime Minister David Cameron who famously promised “the greenest government ever” at the beginning of his term. And equally famously, is reported to have told his aides in November 2012 to “get rid of all the green crap,” – environmental levies that push up energy bills, to bring down costs.

So, where has been the current government in between these two extreme—and self-stated- positions? In the last two elections, the Tories made environment a big election issue, largely in an effort to rebrand, and build their flailing image and even their new logo reflected their stated commitment to environment when they chucked the traditional Conservative torch and adopted a green oak tree in 2006.

They did take some initiatives—such as pushing Europe to a 30 per cent emissions by 2020, taking global leadership in tackling illegal wildlife trade, facilitating the Green Investment Bank, tax incentives for homes using solar energy, and bringing out a white paper on Natural Environment. But most initiatives were not backed with policies, funding or any other enabling factors. For instance, the White Paper was weak on policy and lacked legislative weight. Worse, the green was rapidly turning ‘gray.’ The Prime Minister-and his ministers took to harping on “cheaper energy”—read fossil fuels for Britain, tweaked trespass laws to enable fracking in private lands (“will be “good for our country”, said Cameron, ). There are moves to dismantle other protectionist laws and policy, a major one being the ill-conceived move to sell public-owned forests, though strong opposition forced the government to take a U-turn. DEFRA’s budgets were also slashed substantially by £500m since 2010.

A 2012 YouGov poll showed that “just two per cent of the British public believes that the PM has been successful in his pledge to lead the “greenest government ever”.

To get to the current elections, do environment issues find place in the manifestos, and if so which ones? And by whom, given that all parties do not don similar shades of green?

It seems that Climate Change and energy are the only issues that the debate on environment has narrowed down to; and so it is will continue to be with the United Nations Climate Change Conference, COP21 next year. In fact, in a unique show of unity, David Cameron, Nick Clegg and Ed Miliband, who largely disagree on green issues, have signed a joint pledge to tackle climate change, which they say will UK’s national security and economic prosperity . Yet, confining environment only to Climate Change—however crucial it is, is a sad state of affairs, given its vast scope, encompassing everything from waste disposal to pollution to preserving rare wild species.

There are also sharply polarised debates around Genetically Modified Food and fracking, air pollution and flood control has also been upped on the agenda, given that UK has been severely hit by frequent floods.

Conserving natural spaces, protecting wildlife, restoring habitats are a rare mention. One exception is the highly controversial issue of badger culling—undertaken with the aim to control bovine TB, as badgers are believed to be pass on the disease. With passionate debate both for and against the culling, and with bovine TB taking a toll both on the rural economy, and the government budget (compensation for infected cattle slaughtered was to the tune of £90m in 2011 ); whether political parties are for or against the cull is being watched with great interest.

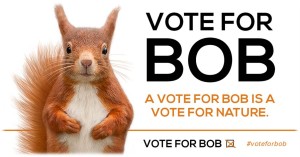

A prominent feature is the effort—largely by NGOs—to engage with political parties to include environment, and nature issues in the agenda. One such attempt is a ‘Vote for Nature’ campaign using ‘Bob’–a red squirrel, the beloved icon of Britain’s wildlife. Driven by one of UK’s biggest wildlife charity, the Royal Protection for the Society for Birds, the campaign seems weak in terms of outlining what exactly ‘vote for nature’ implies, and in strategy and follow-up; but it does its job of hooking voters, and politicians, with over a hundred thousand people, and 87 MPs signing up. There have been other, and more evolved, efforts to nudge parties to go green, notably by a coalition of 10 of UK’s leading environmental groups who call for all political parties to have key environmental pledges in their manifesto. They put forward a ‘Greener Britain’ agenda, listing seven priorities which range from UK taking the lead in the global low-carbon transition, and in the protection of the oceans by championing marine reserves. Domestically, it calls, for recovering the UK’s natural areas and threatened wildlife, setting a strict target on the de-carbonistion of the power sector; greater household energy saving, a new act of parliament and statutory body to oversee sustainable use of natural resources; giving local communities more control over infrastructure and green investments . It is reasoned that a greener Britain would be a stronger, more resilient economy, have stronger communities, exert greater influence internationally.

Yet, while green issues matter, it is felt they do not play a decisive role on whom to cast the vote. Opinion polls suggest that key priorities on the voter agenda are housing, jobs, health (National Health Service), education, economy, immigration. Politicians recognise that and it reflects in their agendas. They know they must do something for the environment, or at least appear to be ‘doing enough’, but do not place it up there with the big issues.

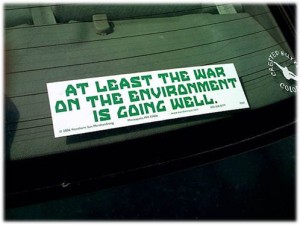

This leads us to another major factor, is that environment issues takes a backseat, when economics weigh in. Or to put it bluntly, environment concerns are considered ‘unaffordable,’ in the pursuit of economic growth, which is what is being played out in the UK today as it witnesses economic stagnation. As the Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne put it, “saving the planet risks putting our country out of business,” an arch comment at environment red tape killing big business.

It gets more complex. A key factor besides immigration (a major issue in the forthcoming polls) which is driving the debate of UK leaving the European Union, is the environment. A significant portion, notably the right wing, of the Tories is pushing for the UK leaving EU, as this will mean the deconstruct of many environment laws including those which govern air pollution, energy, natural habitats, wildlife which are EU governed. Such regulations are equated with environmental red tape, are “bad for business, and best gotten rid of”; is the oft-repeated rhetoric.

The environment has been labelled as a left-wing product, primarily, as traditionally, the only parties that took up environment were the Left-of-centre. So, in a sense, the environment has become symbolic of the left—though the Left, Labour in this case, is not particularly interested in it. In a funny way, or rather, in a negative way, the environment is more important to the Right (wing), than to the Left . Negative, because the dialogue is more about doing away with environment regulations.

This trend is not only about the UK, though. The rise of the more powerful right wing groups and a powerful industry lobby backing them is being witnessed in many countries, including Australia, in the US midterm elections in November, and India, where elections preceded UK by precisely a year. Yet, there has been a parallel rise—though not as significant, of green parties in various countries. Germany has been a stronghold for some years, though the example of the island country of Taiwan is most interesting. The Green Party of Taiwan (there is a loose network of Green parties worldwide). The 2012 legislative election saw the Green Party Taiwan get 1.7 per cent of the party vote, with the highest share—35.7 per cent in Ponso no Tao, largely owed to the anti-nuclear stance of the locals, as the country’s nuclear waste storage plant is located here.

Let us consider the Indian situation. It is almost unfair to compare the two countries, given the vast differences—in populations, demographics, the socio-economic conditions, and one being a developed, and the other, a fast-developing economy. Also pertinent here, is that India is amongst the world’s top biodiversity countries, and has large mega-fauna, while UK, indeed Europe, has lost much of theirs.

So, while not drawing a comparison, a brief commentary is called for, especially considering the shades of similarities in the political rhetoric.

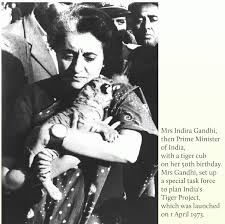

India has over the past decades been very strong on environment and nature issues. Globally, it is recognised as a leader in conservation, having pioneered major initiatives to save endangered wildlife viz Project Tiger. Revering nature and animals is also rooted in Indian culture. India’s leadership position is, however, largely owed to a strong, legal and policy framework to protect, environment, forests and wildlife, backed by political leadership particularly from early 1970s to about 1990.

The erosion of such pro-conservation values began in the early 1990s, which saw India opening up its economy. It is relevant to point out here that this was also approximately the time that neoliberal economic policies were dominant globally . The economic liberalisation processes paid scant regard to environment concerns, more so in the last 15 years. In India, it has now reached a point where environment, and indeed social, laws and regulations, are perceived to be, and openly regarded as “hurdles to the growth”. The move to dilute these has been ongoing, never so much as now, when the Government of India is in the process of reviewing, amending and potentially diluting, key environment regulations.

The environment has never really been a major electoral issue in India, at least not explicitly. Historically, manifestos speak of removing poverty, unemployment, education for all, provision of safe drinking water, providing health care facilities–which do come under the broad spectrum of environment.

This election, the dialogue changed dramatically, with the environment being part of the electoral debate, but largely in a negative sense. Issues like renewable energy, water conservation, ecology-green audits safeguarding the rights of tribals dwelling in forests etc were mentioned by most major political parties (the Congress and the Bharatiya Janata Party, the Communist Party of India (Marxist), and the Aam Aadmi Party). But it was not envisaged how the environment objectives will be met—at best they remained wish lists, especially when they stood in stark contrast to other agendas centred around economic growth, infrastructure, investments—without factoring in social and ecological costs.

In fact, the two main parties-the Congress and the BJP mentioned easier and faster environment clearances processes for industry . The latter, now in power, went a step further, when it stated in its manifesto to “Frame the environment laws in a manner that provides no scope for confusion and will lead to speedy clearance of proposals without delay.”

The above illustrates the commonalties of the environment and development debate in the run-up to the elections, and indeed, in governance itself. Both countries are witnessing a degeneration of environment values, in the quest for high growth. So, while environment is very much part of the electoral dialogue, it is increasingly centered around environment norms to appease big business. Admittedly, there is some noise about ‘taking care of environment’, India gives it a cursory bow. In UK, the mainstream parties—mainly the conservatives and the Labour, do make noises about the environment, and want to appear sufficiently green—even if it ends up as lip service. The key difference in the UK is that there is a push from the electorate, and NGOs to trying to mainstream environment in the election manifestoes in an institutional manner. But how far do governments carry out their commitments, and how much is political double-speak is an open question.

Fact of the matter is, in democracies, it is the electorate that guides politics and politicians, who must always have their finger on the pulse of the people. Unless nature wins itself a large constituency, it will not rate high on the political priority, and its services will continue to be taken for granted, and exploited.

By Prerna Singh Bindra

(This paper was enabled by my Chevening-Gurukul Fellowship). I updated it in early March.

The references have come a little skewed. Apologies.

Bibliography:

1. http://www.forestry.gov.uk/

2. http://www.greenparty.org.uk/

3. http://www.libdems.org.uk/

4. http://www.green-alliance.org.uk/

5. ‘Against Extinction: The Story of Conservation’, William H Adams, Earthscan, London, 2004

6. ‘Future Nature: a vision for conservation’, William H Adams, Earthscan, London

7. ‘Feral: Searching for Enchantment on the Frontiers of Rewilding’, George Monbiot, Penguin 2013

8. “Environment is part of the fabric of the Liberal Democrats’ election manifesto,” Juliette Jowit, theguardian.com, Wednesday 14 April 2010

9. ‘Environment white paper lacks policy, ambition and Defra’s backing, Caroline Lucas, The Guardian, 13 June 2011

10. ‘Greener Britain: Practical proposals for party manifestos from the environment and conservation sector’: Green Alliance, Campaign for Better Transport, Friends of the Earth, Greenpeace, Green Alliance, RSPB, The Wildlife Trusts, WWF; 1 September, 2014

11. ‘UK political parties urged to include green pledges in election manifestos,’ Fiona Harvey, The Guardian, 1 September, 2014

12. Caroline Lucas MP’s speech to the Green Party Autumn Party Conference, 6 September 2014

13. ‘Only 2% believe David Cameron is leading ‘greenest government ever’, The Guardian, Adam Vaughan, 9th March, 2012, YouGov research: https://yougov.co.uk/

14. ‘Fracking ‘good for the UK’, says David Cameron’, The Guardian, 26th March, 2014

15. ‘How the Tories went from oak-tree logo to enemies of conservation,” George Eaton’, New Statesman, 13 September 2011

16. ‘7 reasons why people are turning to the Green party,” James Walsh, The Guardian

17. “We-need-nature-wellbeing-act-protect-wildlife-decline,” George Monbiot, http://www.theguardian.com, Nov 21, 2014

18. DEFRA: Natural Environment White Paper: Implementation update report, October 2014

19. ‘How the Tories went from oak-tree logo to enemies of conservation’, George Eaton, New Statesman, 13 September 2011

20. ‘Cameron: I want coalition to be the ‘greenest government ever’, James Randerson, The Guardian, 14 May 2010

21. ‘Autumn statement: George Osborne slams ‘costly’ green policies’, Fiona Harvey, The Guardian, 29 November 2011

22. ‘You must accept fracking for the good of the country, David Cameron tells southerners’, The Telegraph, 11th August, 2013

23. ‘The Green Party is a growing threat to Labour — could its surge be the next big political story?

24. John Rentoul, The Independent, 15 November 2014

25. ‘George Osborne’s attacks on the environment are costing UK billions’, Damian Carrington, The Guardian, 15 March 2012

26. Industrial pollution ‘costs UK billions each year’, John Vidal and Hanna Gersmann, The Guardian, 24 November 2011

27. ‘Economic Growth and the Environment’, Paper 2, Defra Evidence and Analysis Series, Tim Everett, Mallika Ishwaran, Gian Paolo Ansaloni and Alex Rubin, March 2010

PEOPLE AND ORGANSATIONS I MET WITH (and am very grateful to):

1. Worldwide Fund for Nature-UK (WWF-UK), Wollong, UK

2. Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB), Sandy, UK

3. Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust, Jersey, UK

4. TRAFFIC-UK, Cambridge, UK

5. Environmental Investigations Agency, London, UK

6. Born Free, Horsha, UK

7. George Monbiot, Author, Columnist at The Guardian

8. Bill Adams Head of Department, Moran Professor of Conservation and Development and Fellow of Downing College, University of Cambridge

9. Greg Barker MP- Member of Parliament for Bexhill and Battle since 2001 and Minister of State for Energy and Climate Change 2010-2014.

10. John Vidal, Environment Editor, The Guardian

11. Mark Avery, Author, former Director, RSPB

12. Lindy Sharpe, member, Green Party; Academic researcher on issues surrounding sustainability and industrial food supply

The author is grateful to Jasper Humphreys, Director of External Affairs, The Marjan Centre for the Study of War and the Non-Human Sphere, Department of War Studies, King’s College London, for his mentorship for this project.

I am also grateful to the people and organsations I met with, who gave of freely their time and knowledge and thus, helped me immensely in this project.

My thanks to the King’s India Institute, particularly Dr Kriti Kapila, and Ms Hannah Bond for their guidance and support.

?Additional references

References:

greenprty.org.uk

‘The Green Party embraces left wing populism,’ September 13, 201, The Economist

‘Green Party upto 11 percent in latest Ashcroft poll’, Sebastian Payne, 19 January, 2015, The Spectator

Environment Editor Johan Vidal in an interview

‘Against Extinction’, William H Adams, Earthscan, 2004

[email protected]

‘Green Manifesto zero growth, free condoms no monarchy’, The Week; ‘Green Party’s flagship economic policy would hit poor the hardest,’ Patrick Wintour, The Guardian, 27 January, 2015

‘The Anti-Science Climate Denier Caucus’: A ThinkProgress analysis, 26 June 2013

‘Why is Labour so quiet on green issues?’, Craig Bennett, The Guardian, 22 September 2012

‘Fracking ‘good for the UK’, says David Cameron’, The Guardian, 26th March, 2014

‘MPs concerned over environment budget cuts’, BBC, 7 July 2014

‘Only 2% believe David Cameron is leading ‘greenest government ever’, The Guardian, Adam Vaughan, 9th March, 2012, YouGov research: https://yougov.co.uk/

‘Badger cull mindless, say scientists,’ Damian Carrington and Jamie Doward, The Guardian, 13 October 2012

‘Greener Britain: Practical proposals for party manifestos from the environment and conservation sector’; ‘UK political parties urged to include green pledges in election manifestos,’ Fiona Harvey, The Guardian, 1 September, 2014

Interview: John Vidal, Environment Editor, The Guardian

‘ Nature Unbound: conservation Capitalism and the future of Protected Areas’, Dan Brockington, Rosaleen Duffy & Jim Igoe Earthscan, 2008

‘Little space for conservation in the election manifestos, Prerna Singh Bindra

www.the hinducentre/multimedia/archive/, www.bjp.org/manifesto2014,

www.bjp.org/manifesto2014