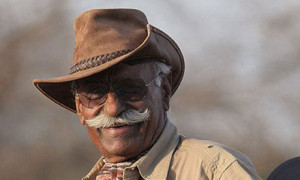

A tribute to Fatji

It wouldn’t have happened if I hadn’t met Fatji. Me becoming—as a forest guard put it—a ‘tiger reporter’. Or maybe it would have, eventually, as I struggled to make ‘wild’ news that did not originate from the urban jungle of Mumbai, where I was stationed. Fatji ensured, in his usual flamboyant manner, that I arrived with a bang. “Do you know,” he announced when I went to meet him, stars in my eyes, “Bumbooram” is missing.”

Who Bumbooram, one would have asked.

Bumbooram: Tiger from Ranthambhore.

So what, one would have asked, especially in those days (it was November 2000,) when the death of a tiger didn’t quite create the media circus it now does.

But I knew of Bumbooram, a huge male tiger from Ranthambhore and quite the star. He was the tiger the then US President Bill Clinton had sighted on his visit to India in March, 2000. “Boomerang,” exclaimed the smitten President in delight (I understand he was as taken by the ‘other tiger’ of Ranthambhore, Fateh Singh Rathore), his American tongue unable to grasp the name Bumbooram.

And now Clinton’s Boomerang had vanished…I penned the story of the poaching of the First Tiger…and so began my tryst with wildlife journalism, tigers, Ranthambhore and Fatji.

Tiger, Ranthambhore, Fateh Singh.

Synonymous.

That’s how he is in my mind, and heart. And so much more.

I remember going to Ranthambhore just after this story broke, It was pretty much my first foray into a tiger forest. I was raw then, all I knew was that I cared. I wanted to help protect the tiger. How could we let it die? What could I do? Could I even do anything? Fatji calmed my nerves. “Enjoy the forest,” he advised, “the rest will happen”.

It was Fatji who acquainted me with the wonders of the wild. Showed me the monitor (lizard), the porcupine, the python, the pitta, the peacock. “Look at him dance,” he exclaimed, flapping his arms, “and for whom,” he added pithily, pointing at the rather drab, and seemingly uninterested hen.

It was here I fell in love with Jogi Mahal, and the huge, imposing and legendary- banyan tree at the back.

But that was before I met the tiger. Or rather the tigers.

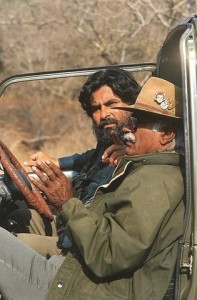

It was Fatji of course, who first caught their scent. Sniff, sniff he went, his Rajput moustache quivering, wicket gleam in his eye. “Tiger, he whispered,” I can smell them.” Where, I wondered, as I peered at a landscape devoid of cat. Sure enough within minutes, our Gypsy was surrounded by four tigers. A mother, and three sub-adults, who arranged themselves around the vehicle, effectively blocking our path for over an hour. No, I did not know fear. I had another tiger in the Gypsy with me!

That day was a Red Letter Day in my life, it divided my life into two: BT & AT Before Tiger and After Tiger. It was a day that set me on a different path, a path unknown, never imagined.

Those who have met the tiger—and Fatji—would know what I mean.

How do I explain what Fatji was? What he meant to me, to those of us he inspired to work for the cause. How do I encapsulate a man’s life in limited wordage… how do you quantify his contribution, or capture his joie de vivre, his work, his commitment, his passion?

Let’s get the basics first: Fateh Singh Rathore was a man of modest education and feudal upbringing and went through a series of jobs—all ending in a bit of disaster (“I was the disaster”, he would chortle) before he was appointed as a ranger in the forest department. In the early days, it wasn’t the forests or its denizens that held his interest, it was his Royal Enfield motorbike. “It was a macho thing”, he explained; though he recalls the time when he scampered—trembling—up a tree when a tiger, curious about the roar of the bike, came investigating!

That changed. And the fear… turned to love.

Perhaps, the first indication of Fateh’s change of heart was his growing resentment of shikar (those were pre-protection days). When he spotted yet another pair of shikari’s tying a machan he decided to act. As the hunters waited at night, bait in place, rifles in hand for the ‘doomed’ tiger, Fateh spoiled the party, leading a noisy procession beating drums, clanging bells and singing bhajans! The Americans went, disgruntled, and the tiger was spared. This was vintage Fateh, always game for a gag, and fiercely protective of his tigers, and Ranthambhore.

What trigged the transformation? “Things changed for me in 1969 when I was sent—coerced, rather—into doing a diploma at the Wildlife Institute in Dehradun (I was convinced it would be a waste of time). I trained under Saroj Raj Choudhary (the legendary director of Similipal reserve, Odisha), and such a great man he was. Those six months changed my life made me view things with a different perspective. I came back to Ranthambhore a new man. My priorities had changed. It was not just about excitement anymore, I looked at Ranthambhore with new eyes”

Ranthambhore he says, was not as you see it now-it was almost barren. You couldn’t see a blade of grass. The cattle that freely grazed inside ate it all-even the leaves that were shed by the dhok tree. Not surprisingly, then, there were hardly any ungulates. You would be lucky to spot a sambar or even a neelgai. There were no lakes, and Jogimahal was a ruin. There were shops, where brisk business continued through the day. At night, if you climbed the Fort and looked out over the entire park, you saw nothing but campfires.

Tigers? You could barely see them, and never in the day.

That changed. And how.

‘Mr Ranthambhore’ devoted his life to the park: he walked the forest with his band of men, laid out the network of dirt roads to facilitate protection, took on poachers, bureaucrats and politicians, patiently won the trust of villagers, persuading and coaxing them to relocate from the park. He cried with the villagers, sharing their grief as they walked away from their ancestral home. Months later, he brought in the headman, who delighted in seeing the tiger walk across what was once their village. The tiger…had come home.

His “real” love affair with tigers began in 1977, with Padmini, a tigress Fatji named after his daughter. He monitored Padmini (“certainly spent more time with her than my daughter, “ said he) more so when he knew she had littered. “Tried as I might, I only got a glimpse of her cubs when they were ten-months-old running across the road, their coats aflame under the glare of the headlight. It was my first tiger family…I fell so much in love, they were beautiful.”

Fatji adored, almost venerated, tigers. He had an instinct-almost a spiritual connection. He could feel, smell their presence. He spoke ‘tiger’. He was a tiger among men; and for the tigers…I am sure, he was one among then.

Under his vigilant, caring eye, the tigers flourished, and shed their fear of man… opening their world, sharing their secrets giving the park the fame and stature it enjoys today. His passion and commitment continued to his dying day. It never wavered-even when he was beaten up, almost to death, in 1981 when trying to protect the forest from grazing; or when he was barred from entering his beloved park by the state, for speaking out the truth that Ranthambhore, and its tigers were dying—being hunted. In 1993 it was Fateh who raised the alarm about poaching in Ranthambhore, even as the authorities continued to cook up tiger numbers.

History repeated itself in 2005, when he alerted an indifferent, antagonistic government that there was a crisis in Ranthambhore again. Tigers had vanished, feared poached. Both times. Fateh paid a heavy price. Politics came into play, he was banned from the park that he that built, revived, and loved, but he fought on. “I will die, someday,” he told me once, as we sat on his balcony, overlooking the reserve listening to the sounds of the forest, “but the tigers, and Ranthambhore must live on.”

It does.

Ranthambhore today is a hub around the tiger—with NGOs, a school, a multi-specialty hospital, a thriving tourism industry, the famous Ranthambhore school of Art that has trained local artists to create beautiful tiger paintings, a hostel for the children of the traditional hunting tribe, Mogyas, to educate them, owing largely to the vision of one man.

Those who say, ‘what difference can I make, I am only one person’, haven’t had the good fortune to know Fateh Singh Rathore: who created Ranthambhore, put it and its tigers on the world map, gave the tigers space, and the star status they enjoy today… and most importantly inspired and nurtured an army of tiger aficionados who battle for its cause.

Fatji embodied the Power of One. He changed the world of the tiger… if the tiger lives today, in Ranthambhore, and in our hearts, we owe it to him. But for Faji it was never what he did for the tiger, but what the tiger did for him. “I owe the tiger everything“, he would say, “they made me what I am today, they made me world-famous.”

On March 1,2011 ‘Mr Ranthambhore’ left us, losing the battle to cancer. The tigers knew they had lost their friend-and champion. At 4 am the next day, hours before the funeral, a tiger appeared behind his house, roaring thrice-maybe in final farewell, maybe to pay his last respects, maybe to reiterate the fact that the spirit of the tiger rested within him, forever.

I shall miss him. Miss going to Ranthambhore—it won’t seem Rathambhore without him. Miss sitting by the fire, listening to hm break into song, regaling his stories, listening to him calling like-and to-the tiger.

I shall miss his concern, his angst. “What are they doing?,” he asked, when the powers-that-be flew Ranthambhore tigers to Sariska, after to fill a sterile forest. Tigers had vanished in Sariska, poached to extinction. “I am not being selfish,” he explained, “but what has been done to make Sariska safe after it lost its tigers? How can they, now put these tigers at risk? Tell me, he demanded, would you give your daughter, if you knew the family had killed their other daughters-in-law? When the first translocated tiger in Sariska, STI was poisoned, I remember his anguish. There were no “I told you so’s” just anger, and pain. “Why can’t they protect tigers?” he said. “Why”

His last phone call to me from the hospital bed was not about him, it was worry over the fate of a tigress with cubs who was out of the national park. “She is at risk, there are villages around, and she has killed cattle. We (TigerWatch, the NGO he founded) are trying to monitor her, and arranged for immediate compensation. But you are in Delhi, please put pressure so that something is done to safeguard her,” he urged.

I shall miss his devotion to the tiger. But more than anything else, I shall miss his remarkable sense of humour, his zest for life that carried us through the worst of times.

There cannot be Ranthambhore without Fatji, but there must, for it is there that he lives on. There will always be a Ranthambhore flush with tigers, it is the only way we can serve the memory of the man who lived for it.