Literary roots of my wild affair

My passion for the wilds –and it is an emotive affair–has literary roots. I devoured book after book, haunting libraries and pavement book vendors (who had the money for new books?). The first ‘animal’ book that piqued my interest was James Herriot with his delightful and thoroughly addictive account of a vet’s life in the English countryside. Not nature writing, strictly speaking. Yet, Herriot had an art of bringing his story animals ‘to life’. His intricate portrayal of his patients and their idiosyncrasies drew you in, and your involvement in his works was complete. Herriot was the first ‘animal’ writer I encountered and he set the ball rolling.

Next was Gerald Durrell, with his fascinating repertoire of books including the absolutely hilarious My Family and Other Animals. There was no looking back after that – and the list of writers-naturalists who have shaped my thoughts and way of life is evolving. There were writers from foreign shores like John Muir, Henry David Thoreau, Walden, Peter Matthiessen who have empowered generations. Rachel Carson was in inspiration – that one woman, and the written word could make a difference, influence an industry, bring in legislation, change had a empowering impact on me. Her seminal work Silent Spring sparked the environment movement as we know it today. The other powerful works came from biologists and conservationists who had done path–breaking studies like Jane Goodall, Dian Fossey and Ian Douglas-Hamilton. Each of them opened a window, and planted a seed but it was the treatise on our native flora and fauna that had me truly hooked. They were more real, they were closer home. The elephants, the lions, the tigers . . . they were, so to speak, in our backyard. In a sense, they were ours—to explore, to experience, and to protect.

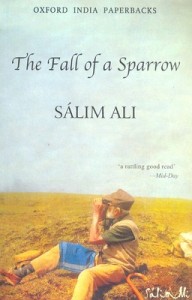

I will not go too far back in history, but must make a mention of the contribution of the Mughal emperors, who comprehensively documented their observations of India’s fauna, notably the founder of the dynasty, Emperor Babar (Babarnama) and then Jehangir, who was the greatest naturalist of the empire. He was an astute observer and his Tuzk-e-Jehangiri has detailed—and animated—descriptions of wildlife. He used several local artists, the most prominent being Ustad Mansur to make life-like drawings of the occupants of his menagerie. The first drawing of the, now extinct, Dodo is attributed to his court. India’s legendary ‘birdman’ Salim Ali explores at length this little known side of the Mughals in The Moghul Emperors of India as Naturalists and Sportsmen.

Game hunters wrote most of our early natural history literature. Shikar has left a mixed legacy in the subcontinent. There is no doubting that hunting played a major part in the decline of wild animals and birds. Yet, in the bygone era, there was no naturalist as ardent as the hunter in pursuit of his quarry. He was well-versed in jungle lore, was a keen observer and kept meticulous records–the latter being especially true of the colonial hunter. Hunting stories may seem out of context today, nonetheless in the annals of natural history they occupy an important and irreplaceable place. They are the chronicles of our vanishing natural heritage, imprinted proof of a lost world.

The early colonial era marked a succession of naturalists, and this growing interest of sharing field observations led to the formation of the Bombay Natural History Society (1883), whose journals are one vast treasure trove. ‘EHA’ or E.H. Aitkin was one among eight founder members of the society, and easily the wittiest naturalist-author of his time. He was unusual – deviating from big game mania, focusing instead on the occupations of the crab and other such smaller creatures with equal finesse and aplomb. He wrote with compassion, entreating the hunter to ‘cherish the tender place in your nature which feels a pang when you pick up the little corpse, so happy two minutes ago’. He warned the collector to beware, ‘lest you begin to feel that a rare bird is not so much a bird but a ‘specimen’. EHA was one of a kind.

James Forsyth, a forester is noted for his seminal Highlands of Central India, in which he mentions, almost in passing, ‘I have several times come across and shot the hunting leopard’. That was in the mid 18th century – a hundred years later, the hunting leopard or cheetah was extinct in India. G.P. Sanderson details the elaborate and cruel kheddah or trapping of wild elephants in Mysore for the royal stable. Shikar lore is almost synonymous with Jim Corbett, an exceptionally fine writer. The legendary hunter was also a pioneer conservationist, who worried about the fading fortunes of the tiger. But one wonders: What is his best-remembered legacy? The Man-eaters of Kumaon continues to a best seller. While Corbett took pains to stress that it was circumstances that made a tiger a man-eater, did his thrilling, almost dangerous accounts leave a sub-conscious impression that all tigers and leopards are dangerous beasts?

Macho hunting accounts, such as those written by Kenneth Anderson, come with another rider, an obsession with big game, and few looked beyond the mega-fauna: tigers, leopard, gaur, elephant, and wild buffalo.

I always had a sense of discomfort with hunting stories – though I understand (I think), that was another era, pre-legislation. I feel an acute sense of discomfort with the idea that hunting was and is, an unequal sport, its ‘Advantage Man’ all along. The idea of viewing free, wild creatures through the barrel of the gun is disagreeable to say the least. Even more so in current climes when yesterday’s ‘game’ faces extinction today. In the age of ecological enlightenment, the yesteryear carnage seems best relegated to the past.

There were many other naturalist-writers. Salim Ali’s autobiographical Fall of the Sparrow and E.P. Gee’s Wildlife of India, served as introductory texts (in the most charming manner) of avifauna and mammals of India. Then came the more contemporary conservationists David Attenborough, George Schaller (another major influence)—and closer home, Billy Arjan Singh (another hunter who took to preservation), and still later Ullas Karanth, Valmik Thapar and of course Sanctuary magazine. Then there were those who may not necessarily be conservationists but are sensitive, established wordsmiths who wrote classics that left an indelible impression in your heart and mind. Ruth Padel’s Tigers in Red Weather, Amitav Ghosh’s The Hungry Tide and Douglas Adam’s Last Chance to See, immediately come to mind.

I have great faith in the power of words, the written word. And books set the stage, formed the foundation of the next stage of life-and career-Journalism.

(I am leaving, for the moment, commenting on the last significant influence in my natural career: the Dog. There is a reason: talking about dogs tends to set me off, and I rarely know when to stop. So for that you must wait another day…)